3. Book: Zen and the Art of Saving the Planet

Part 3: The Way Out is Through, No Mud No Lotus, Engaged Action

Welcome!

I’m so glad you’re here for our buddy read of Zen and the Art of Saving the Planet. In case you’ve missed previous dispatches you can read previous posts here.

This is a space for us, so PLEASE (!!!) leave comments and engage. I want to hear what you think as we go through this content together. Hopefully, I’ll be adding options for live chats and more. This is the early stages of our little community and I can’t wait to see how it will grow.

This Week’s Pages: The Way Out is Through

This week, we’re finishing up Part 1 of Zen and the Art of Saving the Planet. I found this week’s pages to be incredibly relevant for the current moment, especially the reflections on our assumptions around suffering and our responsibility to extend compassion towards our most difficult emotions.

Idea #1: The Way Out Is Through

This week, we're focusing on the empowering notion: "The way out is in." This powerful call urges us to journey inward, using meditation as our compass to navigate the tumult of our collective psyche and mitigate the fears that divide us.

There is no other option but to face our deepest fear and our most painful suffering.

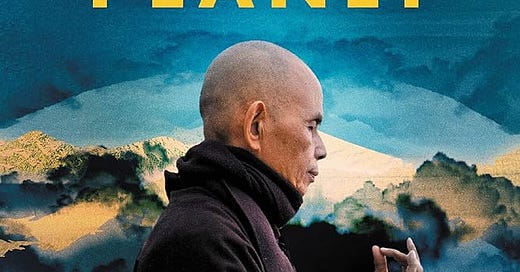

Thay guides us with a gentle but firm reminder: “The practice is to deal with our fear and grief right now; our insight and awakening will give rise to compassion and peace.” It's through the act of meditation that we're able to confront these fears and transmute them into forces of unity and love. Thay’s words resonate with clarity and urgency, emphasizing the need for an internal revolution that can quell the tides of global anxiety.

The wisdom of Thay underscores a critical truth: we have technological solutions that can solve many of our problems, but we don’t use them because of the pervasive shadows of fear and apprehension of people around the world. “We’re not making the challenges a priority; we’re not investing our time and resources; we’re not collaborating,” he notes, pointing to the undercurrents of fear that paralyze progress. Meditation is presented as a remedy to this paralysis, a way to disarm the fears that lead nations to choose arms over altruism, division over togetherness.

In his call for a spiritual dimension to our human problems, Thay eloquently states, “If you can generate the energy of calm, acceptance, loving kindness, and non-fear, you can help offer and introduce that dimension of non-fear and togetherness to the situation.” Here, meditation emerges as the transformative force, capable of nurturing the energies of peace and inclusivity that are so desperately needed in our discourse and actions.

Idea #2: Your Deepest Need

Next, we explore the foundational human need for peace—a prerequisite for clear vision and action. As Thay teaches, this tranquility is as essential as food and water, for "without it, you can’t do anything to help others."

This notion brings us to an introspective inquiry: “How can I myself create the energy of peace, understanding, and of love?” Thay asserts that meditation is the key that unlocks this energy. It's through the art of mindfulness that we can attend to our suffering, understand its origins, and cultivate the love that is urgently needed.

Suffering, Thay observes, is universal. It stems not only from our personal experiences but also from the collective pain of our ancestors and the planet. This interconnectedness of anguish suggests that our inner peace is, in fact, integral to the healing of the world. Thay warns against the temptation to drown this suffering in distractions like music, movies, or games. Instead, he encourages us to have the courage to face and embrace our pain.

Thay’s approach to this inner work is gentle yet profound: “The meditator breathes in, and says, 'Hello, my fear, my anger, my despair. I will take good care of you.'” It is in this moment of acknowledgment and tender acceptance that healing begins. Just as the morning sun coaxes a lotus bud to bloom, the light of mindfulness transforms our inner turmoil.

It’s important, Thay advises, not to be overwhelmed by the weight of this endeavor. Yes, it might be heavy, but like a wave, it will pass. The mindfulness practice is a reminder of the impermanent nature of emotional states and a testament to the strength and resilience we all possess.

Thay leaves us with a powerful affirmation: “If you want peace, you have peace right away.” This statement is an invitation to realize that peace does not need to be a distant goal; it is available in the immediate present, accessed through the breath and the compassionate witnessing of our internal world.

Thus, as we breathe in and out, asking ourselves about the roots of our suffering, we are engaging in an act of profound transformation. We are not just meditating; we are actively participating in the creation of a peaceful inner sanctuary that has the power to ripple outwards, fostering peace in our community, society, and across the globe.

Idea #3: No Mud, No Lotus

The third idea in our reading encapsulates the intrinsic relationship between suffering and happiness, a theme that reverberates deeply in the digital age. The principle asserts that without experiencing the trials signified by the mud, we cannot cultivate the joy represented by the blooming lotus. We're invited to reflect on the duality that underlies our existence.

Firstly, Thay identifies two common misconceptions about suffering: the belief that suffering is all-encompassing and the notion that happiness can only be attained by completely eradicating suffering. Both ideas are pitfalls that can trap us in cycles of despair or fruitless quests for an elusive perfection.

The path forward is a practice, not a destination. Thay elucidates this beautifully: “The practice is to make good use of our suffering in order to create happiness, because happiness and suffering inter-are.”

Thay reflects on the societal tendency to escape emotions through screens. Our digital age offers a plethora of ways to numb or avoid our pain, yet Thay invites us to choose a different route: “Like most of us, I didn’t learn at school how to handle strong or scary emotions." He encourages a turning inward, a confrontation and embracing of our pain, as a path to true resolution.

Mindful breathing, as Thay suggests, is a practice of liberation, a tool to reclaim our inner sovereignty from the grip of anger or despair.

Idea #4: Engaged Action

As we come to the end of Part 1 of the book, Thay introduces us to the essence of Engaged Buddhism, illustrating how spiritual practice can empower and sustain us amid the most challenging circumstances.

This profound teaching emerged from the crucible of conflict of his experience during the Vietnam War: “And so, we had to find a way to practice mindful breathing and do walking meditation while helping those wounded by the bombs—because, if you don’t maintain a spiritual practice during the time you serve, you will lose yourself and you will burn out.” It is a testament to the resilience of the human spirit and a powerful directive for our times—preserving one's inner peace is vital to enduring service.

Thay extends this idea into the principle of the bodhisattva—beings dedicated to alleviating suffering—not just as lofty ideals but as roles we are all called to embody. “The action dimension is the realm of the bodhisattvas," he explains, inviting us to bring sacredness into the everyday.

It's a call to live with intention, bringing depth to our digital interactions, considering how every post, comment, or share can embody the compassionate action of the bodhisattvas. Ultimately, Thay’s vision is one of collective awakening: Every one of us is encouraged to become a bodhisattva, interweaving the ultimate dimension into our present, halting the endless race of doing more, and allowing ourselves to simply be. It's a state of being that enables peace and joy, not just for ourselves but as a shared experience for humanity and the myriad species with whom we share this Earth.

Reflection Questions:

What are some of the difficult emotions you’re avoiding? How are you currently numbing them and could you find an outlet that allows you to express them instead?

How often are you checking in with yourself about your needs during the day?

In the digital age, how can you embody the qualities of a bodhisattva online? How can you bring understanding, peace, and compassionate action to your interactions on digital platforms?

Foushy’s Feedback: On Giving Voice to Anger

Anger is a peculiar emotion. As a woman, society has ingrained in me the belief that anger is unseemly, unladylike, and something to be ashamed of, compelling me to suppress it in favor of being deemed "appropriate."

For many, this upbringing leaves us unequipped to deal with one of our most fundamental emotions constructively. It's too overpowering, too potentially destructive. Consequently, we end up ignoring and suppressing a significant source of energy within us.

For months, I've felt a persistent tension in my chest, as if a rock were being pressed down on my lungs, making it difficult to breathe. I've dedicated countless hours attempting to suppress this feeling, trying to meditate my way into tranquility.

This week's readings struck a chord, particularly the notion of welcoming our anger, showing it compassion, and listening to what it has to communicate. Motivated by this, I decided to experience a rage room—a place where the typically unacceptable expressions of anger are not just allowed but encouraged. Here, breaking things and being loud embody the release of pent-up emotions.

The experience was liberating.

Dressed in protective gear, I entered a room filled with breakable objects like beer bottles and glassware. Initially, my throws were tentative, the bottles bouncing back as if to mock my restraint. But as I threw with more force, the satisfying crash of glass ignited something within me. My heart raced as I reveled in the destruction, item after item.

Next, I was led to another room, this one stocked with electronics, toys, and screens, where I was offered tools of destruction: a baseball bat, a crowbar, a metal pipe. Engaging in this new level of violence, channeling my rage into physical action, was a novel experience for me. As I thought about the sources of my anger and invited it in, I unleashed a fury I'd never allowed myself to express.

The aftermath was a profound sense of peace. My arms were weak, but my breathing eased for the first time in months. That night, I slept deeply and awoke feeling rejuvenated.

This journey into the rage room was an invitation to begin a dialogue with my anger. Moving forward, I plan to explore other physical outlets, such as boxing or MMA to channel and release this energy in order to keep my balance in turbulent times.

I believe everyone should experience a rage room at least once. It's uncivilized, violent, and utterly perfect. It offers a controlled, constructive environment to explore the darker aspects of our emotions without the risk of harm.

Inspired by this experience, I'm considering integrating an "anger practice" into my weekly routine to further understand and manage this powerful emotion.

Once again, thank you Rahaf for sharing this.

These past few years have really damaged my ability to access a kind of inner peace, I'm gradually regaining it but I still have ups and downs, different each time. Sometimes the difficulty is connected to anger, and you're absolutely right in underlining the fact that especially as women we are not "allowed" by society to live this emotion fully. There is a learning curve to it and I am still experiencing difficulty with this emotion. I'm trying to let go of the idea that my anger cannot be constructive but I still struggle on this point. The ideas you shared are very interesting in this regard, thanks!